|

| Black Death |

The Black Death (Black Plague, The Plague, Bubonic Plague) was so named because the skin on many of its victims turned black, a result of massive blood clots. Although there have been many plagues throughout history, the three most associated with the term Black Plague are pandemics (epidemics that affect huge geographic areas) that occurred in Byzantium during the sixth century b.c.e., throughout Europe and the British Isles during the 14th century, and in 1894 in Asia. The first outbreak in 540 c.e., often referred to as the Plague of Justinian, began in Egypt, according to Procopius.

The disease spread from the coasts to inland areas, killing thousands of people each day. Allegedly, corpses were put on ships and sent out to sea to be abandoned. The power shift from south to north and from the Mediterranean to the British Isles is attributed to this devastation.

It was the second pandemic—a series of outbreaks that escalated from an early episode in 1331 to the disastrous events in 1346—that is most frequently referred to as the Black Death. In 1346 a Mongol prince and his armies attempted to lay siege to Caffa, in the Crimea. However, the soldiers were stricken with this dreadful disease and withdrew, but not before catapulting infected corpses over the city wall.

|

The Christian defenders, who thought they were now safe from attack, left to return home but perished from the plague. The few who reached home spread the disease throughout Europe and as far north as Greenland. Within a year 80 percent of Marseille had died. According to various sources, the death rate varied from 12 to 50 percent. It is estimated that in Europe 20–25 million, and throughout the world 42 million people died.

There are three forms or types of the disease: bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic. The most dramatic is the septicemic version. Immense numbers of bacteria cause DIC (disseminated intravascular coagulation), a condition where there is so much debris in the bloodstream, the blood hemorrhages under the skin and the afflicted person’s body, or parts of it, becomes black. These victims died almost immediately, within one to three days after they showed symptoms of the disease.

|

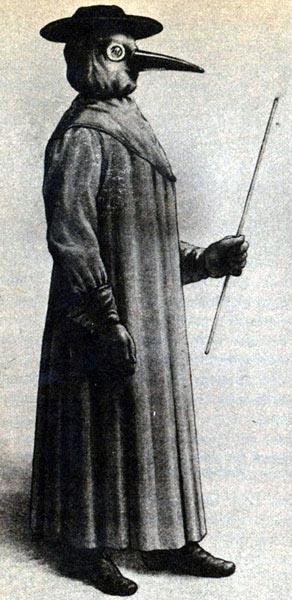

| Plague doctor |

The most painful symptom was swelling of the lymph glands in the armpit, groin, and neck. These enlargements would become buboes, painful abscesses; skin infections filled with pus. When the bubo broke and drained, the purulent material inside was infectious and therefore spread to whomever touched the patient or the anything the patient’s clothing, bedding, or items that he handled.

Boccaccio wrote, “... in men and women alike there appeared, at the beginning of the malady, certain swellings, either on the groin or under the armpits, whereof some waxed of the bigness of a common apple, others like unto an egg, some more and some less, and these the vulgar named plagueboils ... to appear and come indifferently in every part of the body; wherefrom, after awhile, the fashion of the contagion began to change into black or livid blotches, which showed themselves in many, first on the arms and about the thighs and after spread to every other part of the person ... a very certain token of coming death ...”

Patients with the bubonic form spread the pneumonic form via fine droplets from a cough or sneeze. Although it was less lethal than the septicemic version, victims suffered from painful coughing episodes and eventually they coughed so much that the lining of their lungs became irritated and they coughed up blood.

|

People were so fearful of catching the plague that they abandoned their own family members, friends, homes, and public spaces in order to escape contact with anyone stricken with the disease. Doctors who were still willing to treat patients donned hoods with masks, beaks and hats in order to avoid breathing the air around a plague victim. They had no way of understanding the natural history or cause of this disease.

They blamed an unlucky conjunction of astrological influences, such as Saturn, Jupiter and Mars, and poison from the tails of comets, or blamed Jews for allegedly poisoned the wells. But even after the wells had been sealed, people continued to get the plague.

Some of the treatments such as cupping, purging and bleeding, although acceptable in the 14th century, did more harm than good and weakened anyone who remained alive after such insults to their feeble bodies. Amazingly some people survived and because of their illness, developed antibodies that provided immunity against a future attack.

The Spread of the Black Plague

|

| The Black Death ripped through Europe |

This second pandemic was facilitated by a number of factors. Populations had reached such high numbers in Europe that there was not enough food to feed everyone. Consequently those who could not afford the rising cost of food lacked adequate nutrition, and became easy targets for any new threat to health. There were trade routes connecting urban centers and increased travel in the form of caravans. Returning crusaders were spreading Christianity and, at the same time, the plague.

The causative organism Pasturella pestis (now called Yersinia pestis) was already present in the burrowing rodents of the Manchurian-Mongolian steppes but did not create a plague until the black rat (Rattus rattus) spread to Europe with a specific kind of flea. Rattus rattus originated in Asia but reached Europe during the early Middle Ages. They thrived in environments where people lived, near water, and traveled by ship.

The black rat’s flea Xenophylla cheopsis would bite the rat, but instead of being satisfied with its blood meal, its digestive tract would get plugged with plague bacteria, thus creating a constant hunger. It would voraciously bite anything in its path, including humans. When it found a human host, it spread the disease through repeated bites.

Europe had eradicated both the opportunity and the infection, but Asia suffered acutely. In the early 1890s an epidemic broke out in southern China, then in the city of Guangzhou in January of 1894, where 100,000 were reported dead. By May it had spread to the Tai Ping Shan area of Hong Kong.

As in any epidemic high population density, poor hygiene, inadequate health education, and the government’s inability to maintain a decent water supply and sewer treatment facility added to the poor defenses of the population. That year, 2,552 people died. Trade was affected and many Chinese left the colony. Plague continued to be a problem in Asia for the next 30 years.

The causative organism of the plague was not isolated and described until the third pandemic in 1894. Shibasaburo Kitasato and Alexandre Yersin simultaneously discovered the bacteria responsible for the plague, soon after they arrived in Hong Kong to assist in the eradication of the plague there.

Originally named Pasturella pestis, the organism responsible for causing the Black Death was renamed Yersinia pestis after it was reclassified into a different genus on the basis of its similarities to other Enterobacteriaceae species.